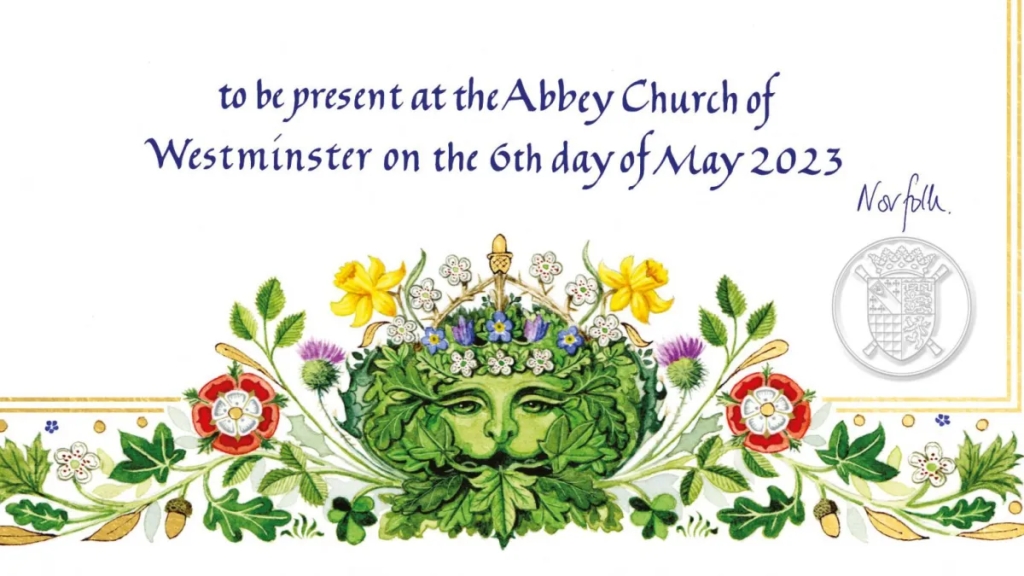

Here in the UK we are finally entering Spring as I write this post where the plants are coming back to life. An image that you will find across the UK, although particularly strongly in England, is that of the Green Man. A floral motif there has been a lot of debate about the Green Man – most of the controversy revolves around an influential 1929 article by folklorist Lady Raglan who argued he was a pagan god that survived through Christianity. We will discuss this more but regardless if he was a genuine pagan god or not he is one now and one deeply associated with British folklore, so much so that he appeared on the invitations for Charles III’s coronation.

The Green Man and Lady Raglan

Depictions of men with foliate heads, (faces and heads made of vegetation), have been a common motif for millennia across various cultures. Historian of paganism Ronald Hutton cites motifs from India dating back 2,000 years as noted examples; the motifs are further found in the Middle East; and across Europe foliate heads cropped up in architecture. However, the specific figure of the Green Man comes mainly from southern England where he is a common motif in churches from the 1300s to the 1600s before reappearing again in the 1800s in the Gothic revival. His image was not, and still if not, limited to churches. In England he is most represented in the country’s most famous institution – the pub. A quick Google search revealed there are at least seven pubs called the ‘Green Man’ in a 35 mile radius from where I currently live. The revival of Gothic architecture also allowed the Green Man to find himself outside of Eurasia with buildings in the Americas and Australia also adopting his image.

The most controversial aspect of the Green Man comes with what he represents. This debate largely stems from a 1939 article by Julia Somerset, the Lady Raglan, who was an amateur folklorist. In her article Lady Ragland argued that the foliate man, the Green Man, was the incorporation of a popular pagan fertility god into the church to appease a local belief. She further argued that other figures in British folklore were manifestations of the Green Man, notably including Jack-in-the-Green of May Day Parades and the Green Knight from Arthurian tales.

The figure variously known as the Green Man, Jack-in-the-Green, Robin Hood, the King of May, and the Garland, who is the central figure in the May-day celebrations throughout Northern and Central Europe. In England and Scotland the most popular name for this figure, at any rate in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, was Robin Hood. There are reasons for thinking that Robin Hood is really Robin of the Wood. Skeat suggests that “wood ” originally meant a twig, and then amass of twigs or bush, so that Robin Hood would be Robin of the twigs or bush, and this would very well describe the headdress worn by the Green Man to this day. We do not know when his cult became established in this country, but by the fifteenth century it formed an important part of the religious life of the people.

Raglan, ‘The “Green Man” in Church Architecture’, 50

She cited this as belonging to an ‘unofficial paganism’ that lived side-by-side with Christianity. This would become an established fact about the Green Man until the 1970s when folklorists and historians began critically looking at the Green Man. Soon enough historians, including Ronald Hutton although he has since nuanced his view somewhat, described Raglan’s work as being based on poor research and reasoning. Emily Tesh is critical of her method but is still praiseworthy of Raglan as someone able to imagine folklore, ‘As a folklorist, Lady Raglan’s historical research skills could have used some work. But as a myth-maker, a lover of stories, a fantasist , she was a genius and I will defend her against all comers.’ It is not exactly an open and shut case. In a series of blog posts Stephen Winick defends Raglan arguing that we have been misinterpreting what Ragland argued, largely because of her own sloppy writing (something she admitted herself). Winick, instead, argues that Raglan interpreted the foliate heads as being pagan in origin, but the people who carved them viewed them as being Christian. This is not too out of the question as Christianity has often presented syncretism with pre-Christian beliefs – most famously the Roman Saturnalia became incorporated into Christmas.

The Green Man and Precursors

We have already discussed that foliate figures have been present throughout history. The UK has other foliate deities independent of the Green Man – the Romans introduced Bacchus who was often depicted among vines; Celtic Wales had Blodeuwedd, a goddess made of flowers; and Somerset’s Apple Tree Man who was the spirit of the oldest apple tree in an orchard. While Raglan’s theory has been criticised you can easily see why some of the figures she mentioned could become reinterpreted as the Green Man – Robin Hood, the Green Knight in the tale of Sir Gawain, and Jack-in-the-Green. This final figure was a popular character during May Day festivals and after appearing in festivals from the 1700s involved of all people chimney sweeps dressing as a green man, or a man covered in vegetation. Jacqueline Simpson is just one of a few folklorists who have cited another potential origin for the image of the Green Man – the Wild Man.

Tracing British folklore via pubs Simpson highlights that during the reigns of the Tudors and the Stuarts (1485-1714) images of the ‘Wild Man’ or ‘savage’ were used to represent the untamed strength of nature. Wild Men were used in pageants and festivals to represent this aspect of the world that so many in the early modern period would have been well aware of, and many of them were dressed in costumes that incorporated leaves and moss. The Lord Mayor’s shows in London utilised them to clear the path for the rest of the pageant and a St. George’s Day parade in Chester in 1610 had men wielding clubs with ivy sown into their clothes to represent the Wild Men. It did not take much for the metaphorical depiction of nature’s strength in the form of the Wild Man to become to literal foliate Green Man. Simpson traces the popularity of the Green Man as a pub icon declining in the 1860s when he was replaced with the more popular figure of Robin Hood – a figure Raglan associated with the Green Man. Stephen Winick has linked the Wild Man origins back to paganism. The Roman god of the countryside Silvanus, Winick argues, helped establish a figure of the Wild Man across Europe – most importantly he was often depicted naked wearing a garland of leaves.

The Green Man and Churches

For centuries images of the Green Man or similar figures were carved into churches across Europe – some of the oldest come from French and Cypriot churches. Part of it can again come from paganism. The head of the Roman pantheon, Jupiter, was often depicted wearing a garland and this made its way into the earliest churches after the Roman Empire formally converted to Christianity. The Palace of Diocletian in Split, Croatia dates to around 300 CE have a Temple of Jupiter where the god is depicted surrounded by foliage. Rather than a continuing pagan belief system we instead see a pagan motif reinterpreted as a Christian one – the foliate head simply moved from temple to church. This brings us to another deity that the Green Man came to represent in the Church: Christ. Like many depictions of Christ the Green Man is bearded and a popular association with vegetation is that they die and grow back every year. As Christ was crucified and was reborn, and with Easter being celebrated in the springtime, it made logical sense to depict Christ among the leaves.

The Modern Green Man

From this we can gather that the Green Man was a motif born through a mixture of popular belief and the legacies of Christianity’s encounter with pagans. However, he is a god today. Neo-paganism, Wicca, and other spiritualist faiths have adopted the Green Man as part of the religion. Being a figure made of vegetation he represents the coming of the Spring and the yearly rebirth of life after the frozen winter months. The Green Man has become so important that he has replaced, or merged with, figures normally associated with May Day – nowadays Jack-in-the-Green and the Green Man are one and the same. The Edinburgh Beltane Festival regularly features a figure representing the Green Man, and other Beltane festivals have adopted him as well. Alongside the Green Man there is Sheela na gig – a naked woman displaying an enlarged vulva that was also carved into Irish and British churches. Like the Green Man she potentially had a pagan birth that became a Christian one and was also incorporated into modern paganism. Both became popular at the same time and were brought into the counterculture of the 1970s: Sheela na gig by feminists and the Green Man by environmentalists (and both for eco-feminists).

Folklore and belief does not have to come from ancient times, they can be recent beliefs. If a piece of folklore is a recent belief it does not invalidate it. When Charles III’s coronation invite depicted the Green Man several folklorists scoffed – the royals had certainly fumbled believing that the Green Man was an ancient British deity but came from a 1939 article. As we have seen, we should not be too quick to entirely dismiss Lady Raglan’s article, but even if we do see the birth of the Green Man being in 1939 this is a very narrow view of looking at national identity and folklore. After all, the British are very proud of victory in the Second World War and the NHS, and you do not need to be a historian to know that these are not from ancient history. Tradition is always invented. It really speaks to the popularity of the Green Man that, if he was invented in 1939 by mistake, he became such an integral part of British identity. Regardless, for pagans and Wiccans the Green Man as a central figure in the coming Spring.

Bibliography:

- Jacqueline Simpson, Green Men and White Swans: The Folklore of British Pub Names, (London: Random House, 2010)

- Lady Raglan, ‘The “Green Man” in Church Architecture’, Folklore, 50:1, (1939), 45-57

- Tina Negus, ‘Medieval Foliate Heads: A Photographic Study of Green Men and Green Beasts in Britain’, Folklore, 114:2, (2003), 247-261

- Bella Millett, ‘How Green is the Green Knight?’, Nottingham Medieval Studies, 38, (1994), 138-151

- Stephen Winick, ‘Introducing the Green Man’, Library of Congress, (15/01/2021), [Accessed 15/03/2024]

- Stephen Winick, ‘What was the Green Man?’, Library of Congress, (17/02/2021), [Accessed 15/03/2024]

- Stephen Winick, ‘Green Man Connections: The Foliate Head’, Library of Congress, (05/10/2023), [Accessed 15/03/2024]

- Stephen Winick, ‘The Green Man: Pagan or Not?’, Library of Congress, (24/11/2023), [Accessed 15/03/2024]

- Stephen Winick, ‘The Green Man, Vernacular Christianity, and the Folk Saint’, Library of Congress, (07/12/2023), [Accessed 15/03/2024]

- Emily Tesh, ‘Inventing Folklore: The Origins of the Green Man’, Reactor, (27/12/2019), [Accessed 15/03/2024]

- Ronald Hutton, Pagan Britain, (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013)

Thank you for reading. For future blog updates please see our Facebook or catch me on Twitter @LewisTwiby.