They might not look like much but the trilobites were perhaps one of the most successful groups of animals to ever inhabit the planet. Very few groups of animals managed to be found over such a long period of time, over such a wide area, and filling so many ecological niches – the only other group as successful and diverse are the insects. Existing for 250 million years and with more than 20,000 species (with more being discovered all the time) it is no wonder that we discuss the ‘Triumph of the Trilobites’.

Discovery and Fossils

The success of trilobites has meant that humans have sort of always known about them. In 1886 a team in France were looking for Ice Age remains near the site of Arcy-sur-Cure only to find that ancient humans were using 400 million year old trilobites as jewellery. This was not a unique case. Ancient peoples as far apart as Australia and British Columbia were using trilobites as jewellery, and medieval Europe and China wrote of ‘swallow stones’ and ‘scorpion stones’. The Ute of Utah referred to Elrathia kingi as ‘little bugs turned to stone.’ This is somewhat accurate as fossilisation involves organic matter turning into stone. The Ute would use Elrathia as pendants to ward off disease and harm. In the late-1600s Reverend Edward Lhwyd described seeing strange ‘flat fish’ which he recorded for study – this would later be identified as a trilobite. It took until 1771 for trilobites to get their name. German naturalist Johann Walch would name them ‘trilobite’ meaning ‘three lobed’ from their body being split into three parts.

Trilobite fossils are so common that you can buy some fossils relatively cheaply. Sites from Utah, British Columbia, Germany, Morocco, China, and Siberia have unearthed some of the richest deposits of trilobite fossils, but many more sites have revealed a treasure trove of trilobites. Not only do we have the trilobites themselves – stomach contents, trackways, and burrows have also been found.

Biology

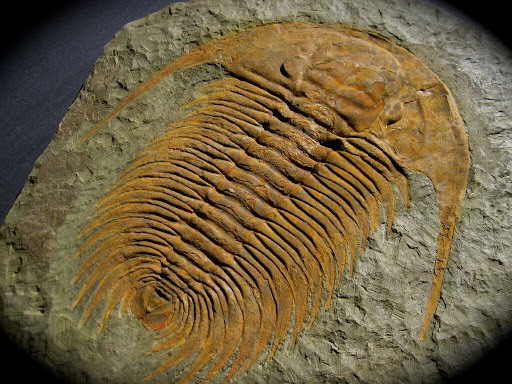

Trilobites came in variety of shapes, designs, and sizes, but they all share a basic body plan. This is where their name comes from. Running down the centre of the trilobite there is the axial lobe surrounded by the two pleural lobes, but they can be divided by three again. We have the cephalon, which is effectively the head, then the thorax, the middle of the body, and the pygidium, the bottom. This simple body plan was one of the key reasons for the success of the trilobites – its simplicity meant it could be adapted to many different environments, so trilobites only had to evolve slightly to adapt to new environments. Trilobites are arthropods, the phylum of invertebrates that also includes arachnids, crustaceans, and the equally as successful insects. Arthropods have a hard exoskeleton made out chitin, a hard polymer, and trilobites have their chitin mixed with calcium phosphate and calcite which is how they have managed to fossilise so well. Trilobites can range greatly in size and to show this I am now going to show you my two fossil trilobites. These two trilobites lived roughly at the same time and place, (Ordovician Morocco), but their sizes varied. The first is a member of the genus Phacops which only fills the palm of my hand thanks to the rock that it is attached to.

Meanwhile, we have a member of the genus Diacalymene which sits perfectly in the palm of my hand as shown below.

The smallest trilobites could easily sit on your fingernail whereas others could become giants. The largest known trilobite species is Isotelus rex, which came from the Middle to Late Ordovician period so 460 to 443 million years ago, and reached a staggering 72 cm (28 inches) in length. Trilobites managed to reach large sizes early on in their evolutionary history with Paradoxides reaching 37 cm (15 inches) during the Cambrian period 514 to 497 million years ago at a time when most other life was tiny. Trilobites are also mostly known for their amazing eyes. Not only were they some of the first animals to develop eyes, but they were some of the first to develop complex eyesight with compound eyes. We can actually tell a lot about the lifestyle of a trilobite based on what type of eye they had. Opipeuter had gigantic eyes that allowed it to have a 360 degree vision indicating it was free-swimming; Neoasaphus had its eyes on stalks indicating that its body was submerged in algae and debris while on the look out for predators; and Ductina was blind indicating it was a burrower.

Trilobites managed to evolve into every niche possible with their body shapes showing this. Many were detritivores, meaning that they scavenged for food on the sea or reef bed, others fed exclusively on algae, some were filter-feeders, and others were active predators. The large size of Paradoxides has indicated that it might have been a predator, scuttling across the reef looking for worms, smaller trilobites, and invertebrates for food. A 2021 paper hypothesised that two species, Redlichia rex and Olenoides serratus from the Cambrian, used their legs to crush the shells of smaller animals before eating them by noticing the similarities between them and modern horseshoe crabs. Similarly, a 2016 paper found trace fossils from Rusophycus whose tracks crossed over the burrows from a worm-like animal indicating that Rusophycus was hunting the burrower. Trilobites were also hunted. Many trilobites, including the famous Phacops, have been found curled up like a woodlouse which would protect their softer underside from potential predators. By the Devonian, 419-358 million years ago, trilobites with elaborate spikes and spines, like Koneprusia of Morocco, evolved to deter any predators. Some trilobites may have even been able to venture onto land. A 2014 paper found trilobite tracks dating to 540 million years ago in Canada indicating that they managed to even make it to the land.

Evolution and Orders

Trilobites first appear in the fossil record around 521 million years ago with a 2021 paper finding the oldest known one to be a member of the genus Parabadiella from south China. This was the Cambrian and is famous for being the era where life first diversified into a wide variety of forms, including the ancestors to every group alive today. This is known as the ‘Cambrian Explosion’, but palaeontologists are now acknowledging that this ‘explosion’ was setup by the earlier Precambrian geological conditions. We do not know from which group of earlier animals the trilobites evolved from, with earlier suggestions that they came from the worm-like Spriggania now seeming unlikely. From the Cambrian trilobites diversified, reaching a peak during the Silurian, but began to vanish through the Devonian. By 358 million years ago the trilobites were reduced to four families, but they continued on until the end of the Permian where the worst extinction event in history wiped them out. This meant that it took 3 of the 5 mass extinction events, and many more smaller ones, to wipe out trilobites! Throughout that time roughly 10 (possibly 11) orders of trilobites emerged. Here I also want to thank the YouTube channel GEO Girl whose video on the trilobite orders helped me get my head around a confusing taxonomic history.

- Redlichiida. One of the oldest of the orders of the trilobites they are noted for being quite flat with an oval shape. Olenellus is one of the most basal trilobites with the segments of their had not fused together. The giant Paradoxides also belonged to this genus. They were found in the early Cambrian until the middle Cambrian, so 524 to 501 million years ago.

- Agnostida. These were incredibly small trilobites, ones that can easily fit on your fingernail. Unlike other trilobites they only had a few segments in their thorax and they were mostly blind entirely lacking eyes. However, they were very numerous and globally widespread (which makes them very good for dating how old a fossil site is). They were also around for a long time from 520 million years ago to the Late Ordovician 444 million years ago.

- Ptychopariida. Another order of trilobites that lived 520-444 million years ago. These were a very diverse order although they have been used as a ‘wastebasket taxon’ where specimens were incorrectly thrown into the one taxon. Mostly triangular in shape they have a distinctive horseshoe shaped glabella with a lot of thorax segments.

- Corynexochida. These are another early Cambrian trilobite but managed to make their way into the Devonian vanishing from the fossil record around 355 million years ago. These had solid and block-like heads with 7-8 thorax segments.

- Asaphida. Another Cambrian trilobite but they evolved later in the Cambrian around 510 million years ago and remained in the fossil record until the end of the Ordovician around 444 million years ago. This is a diverse order ranging from the aforementioned giant Isotelus rex and the stalk-eyed Neoasaphus. Asaphids had more rounded heads and pygidium.

- Harpetida and Trinucleida. Depending on what source you use these are either one order or two. If they are the same order then Harpetida first appears in the fossil record in the Cambrian 490 million years ago and managed to survive until the end of the Devonian 360 million years ago. These are really bizarre trilobites having giant horseshoe-shaped heads with almost now pygidium and thorax.

- Phacopida. We have covered some part of this order in the past, which you can read here. They are one of the best known orders with Phacops and Diacalymene belonging to this order, and are the ones capable of curling up into a ball. First appearing in the Early Ordovician 485 million years ago until the end of Devonian 358 million years ago.

- Odontopleurida. These are unique in several ways. The first, we do not actually know when they first appear in the fossil record, however estimates of the middle Cambrian have been suggested. They lasted until the end of the Devonian. The second, unlike other trilobites Odontopleurida were quite rare. The third, these are the trilobites with the impressive spines and spikes.

- Lichida. These trilobites lived in the Ordovician and the Devonian but were not as common as the Phacopida. Their phygidium were massive, often larger than their heads, and small spikes on their bodies. Like the above Odontopleurida we can see that both of these orders evolved appendages to drive off predators.

- Proetida. If we gage success by time then by far the Proetida were the most successful order of trilobite first appearing in the Cambrian and only going extinct in the Permian mass extinction event 250 million years ago. After the Devonian they were the only trilobites left, although they were rare after this. A big reason for their success was their conservative, barely changing body plan which made them adaptable to different environments ensuring their survival.

Surviving Extinctions

As a class of animals trilobites managed to survive 270 million years on this planet, although this is nothing compared to sponges and jellyfish. Nevertheless, they managed to diversify and become major parts of their environments with it taking three mass extinction events to wipe them out. Each mass extinction event deeply impacted trilobites. The first was the Ordovician-Silurian extinction which cut off the trilobites when they were most abundant, however we do not fully know what caused this extinction event. Global cooling and shrinking of the oceans is believed to have wrecked environments, and we can see that trilobites were impacted. However, with 40% of marine life now extinct it gave trilobites the ability to diversify. This was not the same for the Devonian mass extinction event. A gradual increase in carbon in the ocean, partially caused by newly evolved terrestrial plant matter decomposing in the ocean, caused a significant portion of marine life to suffocate. Trilobites were further impacted by a new arrival in the Devonian: jawed fish. Suddenly things that could bite through their armour so with the deoxygenation of the oceans spelled the almost doom for trilobites. It would be the worst mass extinction event in history that would wipe out the trilobites. The Permian extinction event saw 57% of families go extinct, and with them the trilobites finally vanished.

Bibliography:

- Andy Secher, Travels with Trilobites: Adventures in the Paleozoic, (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2022)

- Riccardo Levi-Setti, The Trilobite Book: A Visual Journey, (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2014)

- Petr Kraft, Valéria Vaškaninová, Michal Mergl, Petr Budil, Oldřich Fatka, and Per E. Ahlberg, ‘Uniquely preserved gut contents illuminate trilobite palaeophysiology’, Nature, 622, (2023), 545-551

- GEO Girl, ‘Arthropoda (Pt. 2) Trilobites – Invertebrate Paleontology’, YouTube.com, (25/04/2021), [Accessed 05/04/2024]

- Ben G Thomas, ‘Triumph of the Trilobites’, YouTube.com, (17/02/2019), [Accessed 07/04/2024]

- Zhiliang Zhang, Mansoureh Ghobadi Pour, Leonid E. Popov, Lars E. Holmer, Feiyang Chen, Yanlong Chen, Glenn A. Brock, and Zhifei Zhang, ‘The oldest Cambrian trilobite – brachiopod association in South China’, Gondwana Research, 89, (2021), 147-167

- Emily Osterloff, ‘How trilobites conquered prehistoric oceans’, Natural History Museum, [Accessed 10/04/2024]

- Tara Selly, John Warren Huntley, Kevin L. Shelton, and James D. Schiffbauer, ‘Ichnofossil record of selective predation by Cambrian trilobites’, Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 444, (2016), 28-38

- Sam Gon III, ‘The Trilobite Eye’, trilobites.info, (01/09/2014), [Accessed 10/04/2024]

- Beth Askham, ‘Some trilobites crushed their prey to death with their legs’, Natural History Museum, (05/03/2021), [Accessed 09/04/2024]

- Russell D. C. Bicknell, James D. Holmes, Gregory D. Edgecombe, Sarah R. Losso, Javier Ortega-Hernández, Stephen Wroe, and John R. Paterson, ‘Biomechanical analyses of Cambrian euarthropod limbs reveal their effectiveness in mastication and durophagy’, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 288:1943, (2021)

Thank you for reading. For future blog updates please see our Facebook or catch me on Twitter @LewisTwiby.